5 Ways Advancement Project’s National Office Shaped Black History

February 27, 2019

February 27, 2019

This year – 2019 – marks Advancement Project’s 20th anniversary. In our two decades of badass racial justice work, we contributed to some major victories for the people. This Black History Month, take a moment to reflect on our legacy and some of the ways we have helped shaped (modern) Black history.

In 1999, a Tunica, Mississippi, plantation owner was developing his land in hopes to bring into the town new homes, a casino, and a school – a plan that would price out Black residents who lived there for generations. Note: the new state-of the-art school would only be accessible to new white residents. Advancement Project responded to concerns about school segregation and we, along with our partner Southern Echo, acted to end the legacy of de facto school segregation and ensure that Black children in the area had access to quality education. We filed litigation against the plantation owner and pitched the story to national media. With national attention on Tunica, the Department of Justice blocked the plan, and in the end, Black families were able to access the new school, giving children the opportunity for quality education.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Advancement Project began responding to stories around zero tolerance in public schools. The term emerged as part of an effort for schools to get “tough on crime” with a national effort to place active police officers on campuses. This resulted in a wave of children facing misdemeanors for mundane, age-appropriate misbehavior. Through national media and public opinion research, Advancement Project showed parents how these policies were hurting their children. The negative national attention forced school officials to move away from zero-tolerance policies. We then helped bring the term “school-to-prison-pipeline” into the national discourse, highlighting the fact that zero-tolerance policies targeted Black and Brown children and pushed them into courts, jails and prisons for minor acts of misbehavior.

Later, in 2018, we released We Came to Learn, a report and tool kit demonstrating that a zero tolerance attitude not only criminalizes young people, but also denies them access to quality education.

In 2014, following protests on behalf of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner in New York City, Advancement Project took the fight against police brutality straight to the White House. On President Obama’s request, we brought local grassroots activists together — the very people standing up to police in the face of riot gear and tear gas — for a meeting in the Oval Office. By creating this channel of communication, we gave the president an on-the-ground perspective on the issue of police brutality from people dealing with it firsthand.

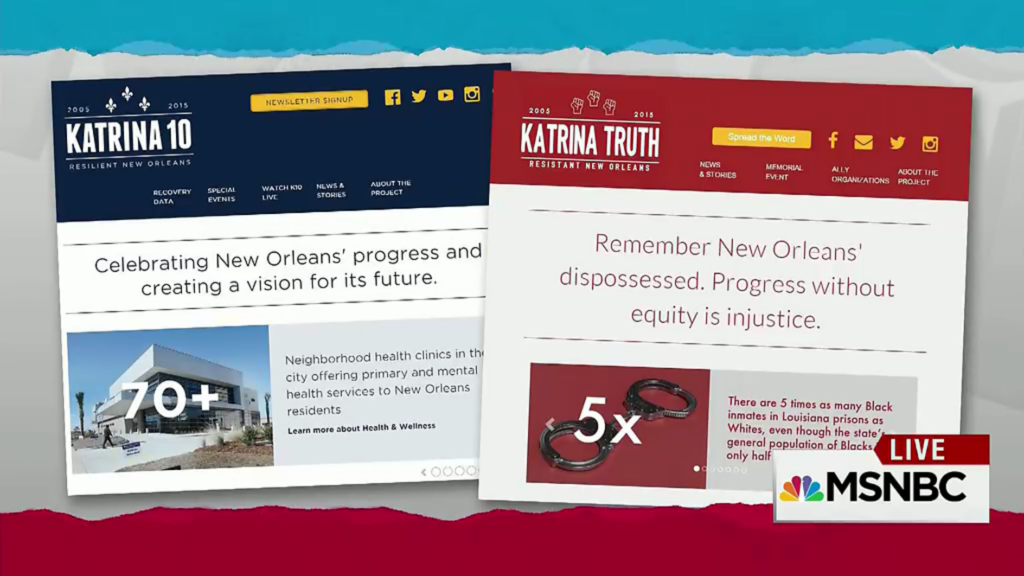

In 2015, we launched the “Katrina Truth” campaign in New Orleans with our partner Families and Friends of Incarcerated Children (FFLIC), in response to the city’s cherry-picked “revitalization” narrative. We created a counter-narrative campaign mocking the city’s official 10th year anniversary website with our own version which highlighted many of the disparities people were still confronted by – a mass incarceration, over-policing, school closures, and gentrification.

After witnessing a proliferation of laws intended to make it harder for communities of color to vote, Advancement Project took action in 2012 to change the narrative around voter protection. We created Talking About Voting, a publication used in conjunction with trainings and webinars to educate communities and progressive groups about their voting rights and the harmful effects of voter suppression for people of color. We trained radio personalities on how to start a national dialogue on these policies, and thousands of people tuned in during their daily commute. This directly resulted in the discourse around free, fair, and accessible elections that we hear today.

In 2018, we took this to the next level by working with Florida’s Returning Citizen population to highlight voter disenfranchisement. In our report, Democracy Disappeared, we cited that more than one million Floridians’ were stripped of their voting rights because of their criminal records. This statewide Constitutional law which disproportionately impacted Black and Brown people also banned those with records from serving on juries and holding office, thus limiting the political change they could bring to their communities. One month after the release of the report, Floridians voted Yes on 4, an amendment which restored the right to vote to 1.4 million previously disenfranchised residents. Yes – 1.4 million people!