Enough is Enough

July 18, 2019

July 18, 2019

If enough is enough, how much is too much?

If enough is enough, how much is too much?

The Supreme Court refused to answer that question on June 27 in the partisan gerrymandering cases, Rucho v. Common Cause and Lamone v. Benisek.

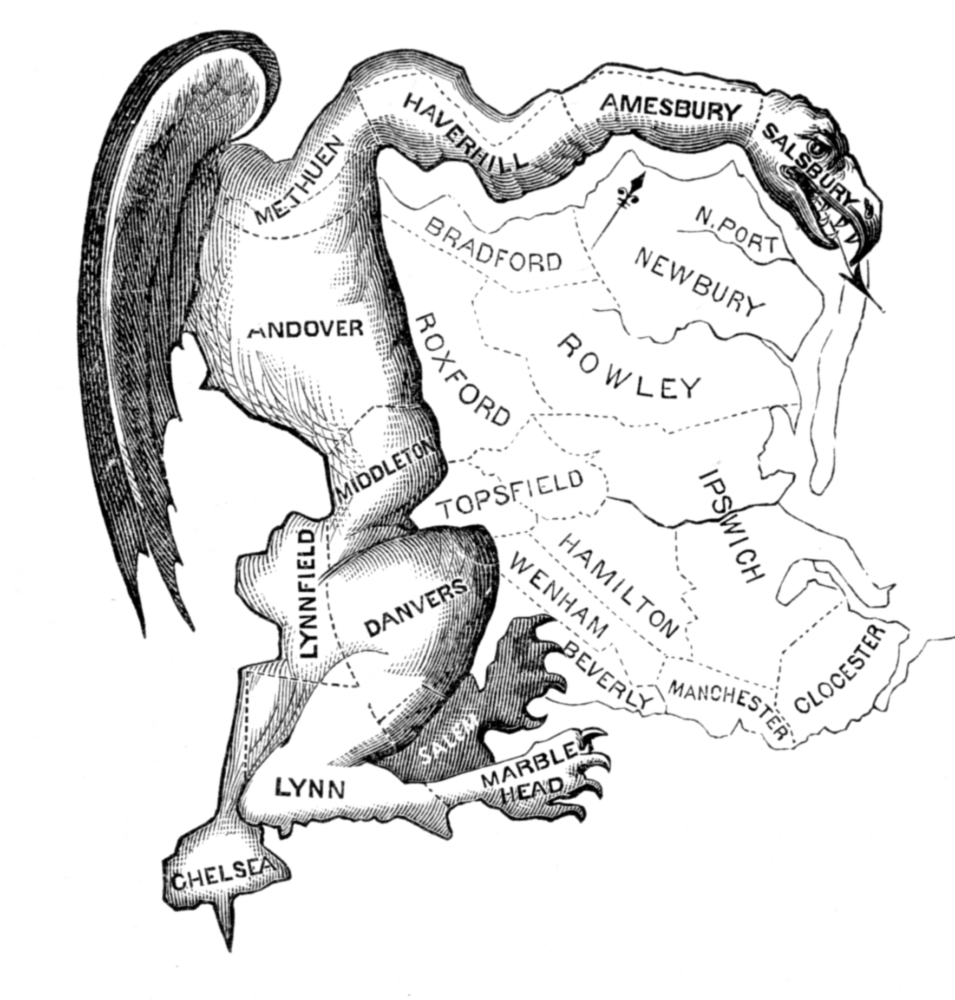

Partisan gerrymandering is when public officials, often lawmakers, intentionally draw electoral districts to favor their party and/or political interests. The practice often results in one party holding a disproportionate number of seats in a state legislature, and dilutes the power and voice of voters based on their race or political affiliation.

The two partisan gerrymandering cases asked the Court to provide guidelines on when enough is enough regarding using partisanship as the primary reason for drafting districts. The Court not only refused to provide limits, it essentially gave elected officials the ability to carve districts any way they choose in the name of partisanship. In the past, the court has issued opinions on when the use of race in gerrymandering rises to a constitutionally inappropriate level, but apparently no such limit exists when it comes to partisanship.

Enough is indeed enough.

In Rucho v. Common Cause, Republicans drafted a gerrymandered redistricting plan in North Carolina. In Lamone v. Benisek, Democrats drew a gerrymandered plan in Maryland. In both cases, the drafters explicitly stated that they intended to draw a plan that advantaged their political party.

The Court, however, found that notwithstanding these proclamations, this was not enough to enter into the “political thicket” of partisan gerrymandering. Chief Justice Roberts wrote, “We conclude that partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts.”

Justice Elana Kagan expressed her discontent with the ruling, “gerrymandering is, as so many Justices have emphasized before, anti-democratic in the most profound sense. Of all times to abandon the Court’s duty to declare the law, this was not the one. The practices challenged in these cases imperil our system of government. Part of the Court’s role in that system is to defend its foundations. None is more important than free and fair elections. With respect but deep sadness, I dissent.”

With that statement, partisan gerrymandering claims are now in the hands of each individual state. A push for redistricting reform must now focus on the state courts and state legislatures to provide safeguards for partisan overreach. This reliance on the states raises the stakes for the 2020 election.

The partisan gerrymandering ruling provides a clear focus on legislative and congressional elections in 2020. Here’s how: persons elected in the 2020 cycle will draw the districts for elections held over the next decade. In 2021 after states receive the Census count for their states, counties, cities, school boards and other jurisdictions, the redistricting process begins. This time, it will occur without the federal oversight that Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act provided and with those elected officials understanding that the federal courts will not review their “undemocratic” efforts to game the system in a way that provides an unrealistic advantage to the elected political party. This makes the election in 2020 extremely important – not just for the Presidential Election, but for democracy.

Enough is enough.

Gilda R. Daniels is the Litigation Director for Advancement Project National Office